|

| Elmore and Raylan At least we still have "Justified" |

And my love for MacDonald and his Knight in Rusty Armor eventually led me to Elmore Leonard. Though his first Detroit crime book was City Primeval, the first Leonard novel I read was “Split Images”. And my mind was absolutely blown. Here was something different, weird and quirky and yet disturbingly recognizable, the actions of brutal, greedy men in their own little milieux, casually wrecking the lives of friends, neighbors and loved ones. Here was people talking to one another in comfortable rhythms, speaking of the banal and the horrific in the same paragraph. The only thing close to it was “The Friends of Eddie Coyle”, but this wasn’t greedy small-time mafia thugs, this was smaller time and objectively crazier people, circling and jostling each other in small orbits.

That juxtaposition of life and death writ small, a world where a casual contact one day could lead to a bloody confrontation the next, where a man could decide to bet it all on a desperate grab for a big bag of cash, where threat and menace could be the clear subtext of a mundane conversation. While I loved Split Images and immediately set out to gobble up the entire Leonard library, it turned out that the rest of his work was, in an odd sense, gentler than my first sip at the cup. Split Images was a harsh, brutal story, punctuated by the classic Leonard wit, and occupied by the kind of off-center and even distinctly unbalanced characters that are simultaneously the most fun to create and the hardest to carry off. I went back to the beginning, and I read “City Primeval”.

If you have never read it, stop what you’re doing right now and order it. Because, remember, this was his first work outside the Western genre, and the climactic scene, in a kitchen with spoken and unspoken narrative around the refrigerator, a couple beers and a bottle opener seems banal, even friendly. But it is a deadly confrontation, and the underlying reality is two men trying to position themselves to get the jump and shoot the other dead. It is classic Elmore Leonard in every way, a kind of scene you see played out time and time again in his novels, his movies and in Justified, the television series he created with his quirky US Marshall Raylan Givens as the lead character, and a classicly twisted foil in Boyd Crowder, played by the endlessly mesmerising Walton Groggins. The only thing I have ever read that comes even close to that climactic set-piece in City Primeval was a scene in a cantina in the incredible, though sadly out of print R. Lance Hill novel “The Evil That Men Do”. I doubt if you can find it, but if you can you’ll be quite glad you did.

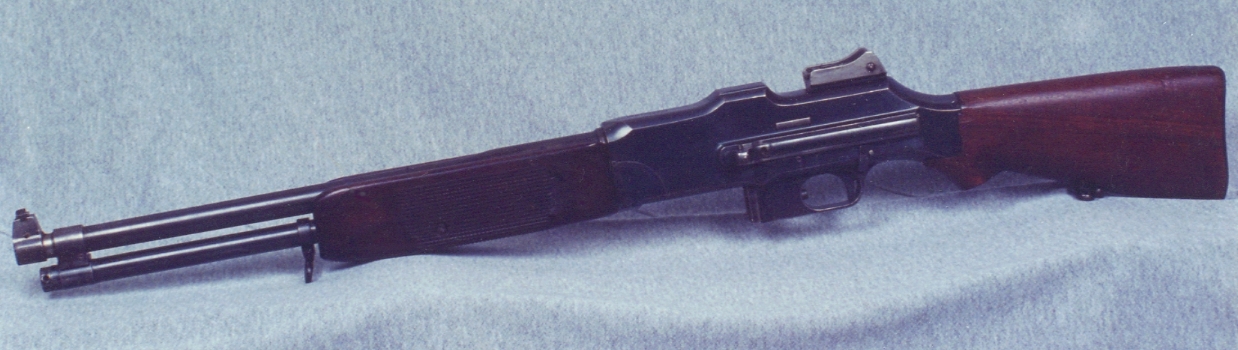

In 1976 Elmore Leonard introduced us to Frank Ryan, ex-con, professional armed robber and the author of the Ten Golden Rules for a successful career in armed robbery. If there was any doubt remaining, that closed the deal for me. Here was everything I wanted in a novel - primarily no freaking “good guys”, just bad guys to root for and bad guys to root against. A protagonist who was a thief, whose life goal was to be a successful thief and who was willing to develop and enforce a set of discipline and rules around that goal. A thoughtful and careful thief, sure, but one who willingly chose his life without regret.

Elmore Leonard went on to garner great fame and fortune, unsurprisingly in the movies, where his dialog-heavy stories lent themselves so ideally to that kind of format. From Travolta in “Get Shorty” to Tarantino’s “Jackie Brown” to Clooney and Lopez in “Out of Sight” to even Russell Crowe and Christian Bale in “3:10 to Yuma”, a 1953 Elmore Leonard short story, his successes at the box office dwarf his reputation as an author. But if you want to see inside the mind - and the heart - of Elmore Leonard, go back to those early crime novels, City Primeval, Split Images, Swag, and Unknown Man #89. The settings were richly detailed, the City an actual character in the books, the characters deeply human and nuanced, and the stories were kinetic and plausible.

A few weeks ago, Elmore Leonard had a stroke, and on Tuesday he died in his home outside of Detroit at the age of 89. He was a master of the American novel - not seeking to produce some kind of classic literary prose but rather the novel in it’s purest form - the novel as entertainment. He wrote stories people wanted to read, set in places and occupied by characters that were at once familiar and exotic. His mastery of the American dialect - North, South, Black or White - lent a powerful realism to his dialog. You can see his influence in people from Quentin Tarantino to Aaron Sorkin, and as he famously said in his 10 Rules of Writing, “if it sounds like “writing”, rewrite it”.

His loss is a profound one for the millions he has entertained for decades, a unique American literary voice that might be equalled, but can never be replaced. Thank you, Mr. Leonard, for all the hours of joy you gave me, for the insight into what the written word can be, and most of all, the understanding that big things happen in small places, and the magnitude of the event is measured locally, by the people it impacts.

...